Damon Albarn | Record Collector – April 1998

Main article typed up by Chris Lyons on Blur Point, see the scans above for the full version.

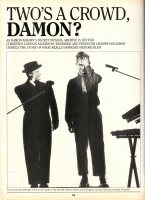

Two’s a crowd, Damon?

As Damon Albarn’s secret musical archive is set for Christie’s London Salesroom, engineer and producter Graeme Holdaway unveils the story of what really happened before Blur.

The official Blur story goes like this. Damon Albarn leaves East 15 drama school, throws himself into the world of art, forms what we once described as “a soul synth duo called “Two’s A Crowd”, gets a shortlived job in a recording studio, then joins forces with Graham Coxon, Alex James and Dave Rowntree to form Seymour in the summer of 1989. At the end of that year, they send Andy Ross of Food Records a four-track demo tape, he signs them up in March 1990, and persuades them to change their name. Ahead lie “Modern Life”, “Parklife” and, of course, the mighty “Blur”. As ever, that story barely scrapes the surface. A giant cache of demo tapes, masters and work in progress, due to be auctioned at the end of this month by Christie’s, reveals the secret history of Damon Albarn’s musical apprentice-ship. For two years, it transpires, he was managed, coached and recorded by the operators of a central London studio called The Beat Factory, in Euston. A 24-track studio, The Beat Factory was owned and operated by engineer and producer Graeme Holdaway, and his then partner Marijke Bergkamp, from August 1984 until its demise in late 1993. Its client list included some of the most famous names of the period. Holdaway was the main resident recording engineer (he’s now a freelance engineer, producer and musician); Bergkamp was the studio manager throughout the Damon era (she’s now a video and film editor, whose recent credits include Mission Impossible and Rob Roy). As a production team, Holdaway produced artists, while Bergkamp managed them. Together, they shepherded Damon and associates through Two’s A Crowd, a period as a solo artist, Circus and on into Seymour (only a live tape by them is being sold at Christie’s; their studio master-tapes are owned by EMI). The four tracks that Andy Ross heard were just the tip of the iceberg: Holdaway recorded no fewer than 40 songs during this unheralded period, including the first version of Blur’s debut single, “She’s So High”. In this exclusive account, Graeme Holdaway reveals the secret history of a 90s rock institution…

Damon Albarn walked into The Beat Factory one day in October 1987. He told us that he had asked around for the best recording studios in that part of London, though I later discovered that he had done no such thing, but just visited the first studio he found in the Yellow Pages. He was 19 at the time, and had decided to leave East 15 drama college after a year, to concentrate on his music. He was nail of boyish enthusiasm, while trying (sometimes unsuccessfully) to maintain an air of know-it-all nonchalance and cool. He had some money to spend on demos, so we talked through exactly what he had in mind. We did the first session for him as a regular client: he paid the standard rate for the studio. I sequenced the songs on computer, and selected samples of drums and other instruments on various keyboards, while he played the various parts onto computer. He was a pretty good pianist, as he demonstrated on the studio grand, but hadn’t yet adapted his style to the lighter touch necessary for keyboards and synths. After we’d ‘sequenced’ the songs (one of which, I remember, featured an instrumental ‘drone’ from an Eric Clapton soundtrack to the BBC thriller Edge Of Darkness), we added the lead vocals. I think I may have played guitar on one of the tracks, and then we mixed them.

ENERGY

The songs weren’t that great – I can’t even remember the titles at this remove -but what came across was his energy, and the feeling that here was someone who might the able to have a career in the music business. OK, it’s easy to say that in the aftermath of “Parklife”, but the fact is that My partner and I were the only people who believed in Damon for two-and-a-half years. It is incredibly difficult to break new artists even if they have a ‘commercial’ sensibility, let alone if they have the sort of individ-uality, quirkiness and bloody-mindedness of someone like Damon. After the session, my partner Marjjke and I had a difference of opinion about him. She heard the songs, but while she agreed with me that they weren’t that great, they had their moments, and she felt very strongly that he had a quality about him – the air of a promising artist whose songs would get better if he were stimulated in the right way. I secretly agreed with this, but had my doubts about the working relationship. She hadn’t done the session with him, and I felt wary of Damon. His enormous energy seemed to change direction at a moment’s notice on a whim, and he tended to be something of a musical fashion victim. I also remember feeling slightly tired at the prospect of the enormous amount of work that would need to be put into his music. The fact that he was a solo artist entailed that he would require enormous practical input, in terms of knocking his songs into shape, sequencing them, organising musicians, and overseeing the sessions, besides producing and engineering them. After much debate, we asked Damon to come up to the studio from his parents’ home in Colchester. We discussed a production and management deal, agreed principles, considered the next moves, talked about music, and gave him a lift back to Liverpool Street station.

CONTINUITY

During the ensuing weeks, Damon and I worked on a number of songs, including “Bitter Sweet”, “China Doll” and “The Red Club”, usually starting with rough piano and vocal takes which we then sequenced into the computer. My aim was to get Damon to settle on a style with which we could establish some sort of continuity. In hindsight, maybe that wasn’t the right approach: maybe I should just have given him his head to be as experimental as he liked. But I found it a bit perplexing that he would sound like Bowie one minute, Morrissey the next, and then write a good approxima-tion of a Kurt Weill song. Throughout his time with us, he was a musical chameleon. Sometimes he would retain one style consistently enough to write and perform a batch of songs of about album length, as he did with his later band, Circus. But early on, groups of two or three songs would hang together stylistically, before he would completely change his approach. He ranged from solo piano/vocal songs to very synth- and sample-orientated tunes and full-on, two-minute punk thrashes – plus a few songs with luscious string arrangements with echoey sax solos and heartfelt vocals to match. He also wrote a song with African percussion and world music influences, called “Free The World”.As a result, it was difficult for Marijke, as Damon’s manager, to choose which approach to take to record companies. We would find ourselves touting around a three-song set of demos when we knew that Damon had already moved on to a new musical phase.

A few weeks into the process of writing, arranging and recording new songs, Damon threw us the first of many curved balls that were to be lobbed our way in the course of our association with him. A guy called Sam Vamplew had been working in The Beat Factory as a client; he had a financial backer, and we were recording a number of his songs at the time. Sam met Damon in the studio and they decided to join forces – Sam, effectively, becoming a partner in Damon’s deal with us. We definitely didn’t like the idea. Marijke in particular was dead against it, and we both argued the point with Damon. From our perspective, Sam wasn’t a suitable foil for Damon’s talents – as Damon agreed once the liaison had fallen apart, a month or so later. It was not that Sam was not talented – far from it, as he had a fine voice – but his songwriting didn’t seem to fit ideally alongside Damon’s. As it was supposed be an equal partnership, that meant co-writes, or at least an equal number songs written by each partner, which was not that attractive a prospect. Suffice say, a set of songs was recorded – some Sam’s that we already had backing tracks for, and some of Damon’s that we had been stockpiling – under the name Two’s A Crowd.

We hired a backing singer and sax player and recorded and mixed the songs. They included “Reck Me”, “Let’s Get Together”, “Big Religion”, “Can’t Live Without You”, “Since You’ve Been Gone” and “Running”. A photo shoot was arranged (some shots from which surfaced years later in Smash Hits), packages were prepared by Marijke, record companies were visited – and the partnership fell apart. Damon was later to claim in the press, in one of the few times that he has alluded to our involvement in his career that the whole partnership was dreamt up by us. Not so. We picked ourselves up, Damon included, rethought, re-jigged and carried on. Sam was removed from songs that were mainly Damon’s, Damon was removed from songs that were Sam’s, and the artists carried on separately. I am sure Damon learned something from the experience, and the increasing maturity of his next batch of songs perhaps points to this. Numbers like “Free The World” and “China Doll” show an artist beginning to make the link between what he is feeling and his performance. His voice was also beginning to mature, perhaps because of the large amount of singing he had doing since he met us. He then acquired his own sequencing set-up at home, and came up with some different kinds of songs, including the dark and moody “Black Rain Town” and the more straightforward “Drive” and “Heaven”. He also worked in the studio with our other engineer, Richard Ashley, which took some of the pressure off me.

DEVELOPMENT

A lot of development work was done over the next few months, but we didn’t record anything properly until May 1988 because Damon and I were looking for distinctive ‘sound’ or direction to follow. We set up in the recording area of the studio with a cheap drum machine, a keyboard, and a bass and/or guitar, and then experimented with drum grooves, simple bass-lines and top-line vocal melodies. After his experience with Sam, I knew that Damon needed a foil, or at least a sounding-board – which is why, temperamentally, he is best suited being in a band. That was the role I tried to perform. I had played guitar in bands in the past and always had instruments in the studio that I played regularly, so I could help with the process, especially as I could then transfer the rough ideas to computer and flesh them out into a fully-fledged arrangement. Marijke would listen to the blueprints and give feedback about which ones she thought were working, and which were not. She wasn’t one to mince her words, which sometimes upset Damon, but she had good instincts, and would almost always be vindicated by Damon coming out with the same opinion as her two weeks later, as if he had been the first to reach that conclusion. By May ’88, we had a number of songs ready to record, in a style we called ‘Jazz Punk’.

The best of these songs, according to everyone who heard it, was a number to which I had contributed enough musical ideas (the bassline and a portion of the a melody) for Damon and I to agree that it was a co-write. That was “Hippy Children”, which contrasted the lifestyle of the previous generation with the 80s manners Of their children, summed up by the Oscar Wilde paraphrase: “We are all looking at the stars, while the hippy children hang around wine bars”. This was to have a significant impact later. We recruited the guitar skills of a young salesman who worked in an instrument shop in Denmark Street. His style, like a speeded-up Van Halen, made an interesting contrast with Damon’s vamping piano technique. We so used the same saxophonist who’d played on the Two’s A Crowd sessions. More signficantly, these recordings also marked The professional studio debut of Damon’s old school sidekick, Graham Coxon. The only difference was that he was playing saxophone!

CIRCUS

The project name that Damon coined for this stage of his career was Circus. We packed up the songs once more, and did the rounds. The feedback that we got was that while the record companies really liked Hippy Children”, they weren’t sufficiently pressed by the other songs to get involved. The implications sank into Damon, and did me damage. I thought I could see him thinking to himself, “What kind of artist am I If the song the record companies like is the The one I co-wrote with my producer?”. Martjke, however, considers that he had just seen the need to surround himself with a band. We could see his point, though I admit that I had a bad moment when he immediately changed direction again and abandoned the mode of writing that I thought had been on the verge of bearing fruit. In any event, Damon realised that if he was going to work properly as an artist, he needed a proper band, and so the second incarnation of Circus was created. Circus the band was a significant develop-ment towards the way in which Damon would eventually greet the world. Not only were they a functioning band, but they contained a computer operator for Colchester Council called Dave Rowntree on drums, and trainee shoegazer Graham Coxon on guitar and occasional saxophone. During his earlier session, his guitar skills hadn’t even been mentioned, but when I heard him play, I immediately lent him my own custom-built expensive jobbie and was amazed at his natural talent. He was looking for an amp as well, so I fixed him up with one from an electronics designer friend of mine, after which he could deafen at fifty paces.

TENSION

Despite these moves in the right direction, this line-up was not without its problems. In particular, there seemed to be some tension between Damon and Eddie Deedigan, acoustic guitarist, songwriter, and erstwhile East 15 drama school student. As with Two’s A Crowd, Marijke and I were not wholly convinced that this was the right direction for Damon. Working with him also had its drawbacks. He had gained in confidence, and a certain strain had arisen between Marijke and him, partly I think because of the lack of response from record companies. He never looked at himself or his art for the cause of any problems, and given the fact that we were still committed to running The Beat Factory as a commercial facility, it was probably inevitable that there would be conflicts. But the main problem centred around the rivalry between Damon and Eddie Deedigan. Factions arose between Eddie and his mate Dave the bassist on one hand, and Damon, Dave Rowntree and Graham Coxon on the other. Both Damon and Eddie were songwriters, but once again, it was obvious to us who was the better. Only one song of Eddie’s made it to the recording stage when the songs were routined. At first, the tension only manifested itself as a lot of mickey-taking on both sides, some, of which was hilarious and almost existential, but Eddie – being more articulate -had the edge, and usually the last word. I felt that this resulted in Damon becoming more negative in his dealings with the band, and with Eddie in particular.

FLIPPANT

After the songs were mixed, a gig was arranged in South London. We helped the band set up, they came on stage – and then Damon and Eddie spent the long gaps between songs being flippant and taking the rise out of each other. Marijke was extremely angry, perhaps because she had seen it coming. There was a showdown after she and I expressed what we thought of the gig. The Eddie Deedigan faction unceremoniously quit the band. Damon kept out of the argument, but probably wasn’t displeased by the result. About this time, something happened that caused problems between us and Damon. We had been in contact with a music publisher who had met Damon and heard the material. The publisher asked if we would let Damon see him alone. We felt OK about this, so we let him go to the meeting. We were worried when we didn’t see Damon for a few days. Eventually he turned up at the studio and wheedled out of him that, in time-honoured music business style, the publisher had done is best to destabilise our relationship with our artist. Damon found this very disturbing, and it knocked his confidence. The publisher was very unprofessional in his approach, and I think Damon drew conclusions that were rhaps not the best start in professional life for a young artist.

SEYMOUR

This left Damon, Graham and Dave. Either Graham or Dave had already met Alex James, a bassist, who was allegedly studying French on the south coast. He said a few years later: “I thought Damon was a bit of a prat, but he had the keys to a recording studio”. So he joined, and the line-up that would become Blur came into being. But they weren’t called Blur yet; that was Food Records’ Dave Balfe’s idea. They were called Seymour. This was the most stressful time that I had while working with Damon, but it was also the period when Marijke and I pulled out all the stops and worked most effectively with the result that Damon got a deal. The music made by Seymour had a lot of the same elements as the first Blur album, and some of the same songs, including “She’s So High”, which retained an identical arrangement. Some people seem to assume that Seymour was a completely different entity from Blur, with a different line-up, but it was all of the same musicians with some of the same songs. It was the same band. Initially Damon in-sisted on arranging gigs himself and organising the publicity. After two weeks of struggle he came to Marijke and asked if she would organise them.

The Seymour recording sessions were very intense and quite emotional. Damon was at his most forceful about the direction he wanted to go in. I can’t honestly say that I produced the sessions, although the songs that surfaced as additional tracks on the Blur “Sunday Sunday” EP – “Dizzy”, “Fried” and “Shimmer” – credit me as producer. I certainly engineered them, but Damon would brook no interference, and I felt he compromised the overall sound by only singing with a cheap microphone right next to the band at full thrash. We ended up with so much of the band on the vocal track that it was almost unusable. This was nothing compared to the traumas that we went through during the mixing. Besides my difficulty in working with Damon, even Graham was asking for things that, in my opinion, worked against the strength of the tracks. I incorporated their ideas as best I could, but eventually I had to kick them all out of the control room in order to get the songs mixed. Five songs from the sessions were put onto a copy master, and Marijke once again did the rounds of the record companies. This time she got some press and gigs lined up, the sort of thing that is much easier with a band. They played the Camden Falcon and the Bull & Gate, and by the skin of our teeth we won them a support for the New Fast Automatic Daffodils at Dingwalls. Marijke went to see Dave Balfe and Andy Ross at Food. Andy Ross came to many gigs and eventually Dave Balfe came to the Falcon. They both felt that the band had a future.

CONTRACT

It was not long before Christmas 1989. Our management contract with Damon was up for renewal. Perhaps naively, we assumed that because we had done all this work for him, he would remain loyal to us. Unfortunately not. He refused to re-sign and basically walked out. After Christmas, we read in the music press that Food Records had a new signing: Blur. Every artist in the public eye revels in the glory of being there, but for every visible figure there are a hell of a lot of skilled people in the background, sometimes making crucial contributions. We know that we did the right thing with our artist, because his subsequent career has proved that to the world. I think our main contribution was to give him the freedom to develop at his own pace, a luxury few artists were afforded at the time. If you listen to the songs, it is somewhat like listening to his later career in miniature – which is what gives this tape cache its fascination.